Overview: A Visionary’s Quest

Thomas Townsend Brown (1905–1985), an American inventor and physicist, dedicated his life to exploring electrogravitics, a field he believed could unlock anti-gravity propulsion. Starting in the 1920s, Brown’s experiments with high-voltage electric fields led to the discovery of the Biefeld-Brown effect, where asymmetric capacitors, charged with 25,000 to 200,000 volts, produced a mysterious propulsive force. He envisioned revolutionary applications, from aircraft to “space cars,” positioning him as a genius who dared to challenge conventional physics.

Mainstream science attributes the motion of Brown’s devices, like his gravitator and disc-shaped lifters, to electrohydrodynamics, or ionic wind, where charged particles move air molecules to create thrust. Vacuum tests showed no force, debunking anti-gravity claims. Yet, Brown’s meticulous experiments, detailed patents, and influence on alternative science communities highlight his brilliance. Some speculate his work inspired secret military technologies, though evidence is scarce, fueling fascination with his ideas.

Brown’s legacy endures through amateur experiments and ongoing debates about advanced propulsion. His ability to bridge electricity and gravity, even if unproven, marks him as a visionary whose ideas continue to inspire those exploring unexplained phenomena and non-human intelligence (NHI) technologies.

Early Life: A Prodigy’s Spark

Born on March 18, 1905, in Zanesville, Ohio, to a prosperous family, Thomas Townsend Brown showed an extraordinary aptitude for electronics from a young age. His parents equipped a private laboratory in their Pasadena, California home, fostering his curiosity. At 16, in 1921, Brown noticed an unusual effect while experimenting with a Coolidge X-ray tube: when high voltage was applied, the tube’s mass seemed to shift based on electrode orientation, suggesting a link between electricity and gravity. This observation ignited his lifelong pursuit of electrogravitics.

Brown attended Doane Academy from 1922 to 1923 and briefly studied at the California Institute of Technology in 1923, where his unconventional ideas clashed with the curriculum. A prominent physicist dismissed his electro-gravity theories as impossible, prompting Brown to leave after a year. At Denison University in 1924, he claimed to work with Dr. Paul Alfred Biefeld on the effect later named after them, though no records confirm this collaboration. Brown’s early independence showcased his self-driven genius.

By 1927, he filed a patent for a method to produce force or motion electrically, aiming to control gravity. In 1929, he published an article in a popular science magazine, describing his vision of propulsion for ocean liners and futuristic vehicles. His early work, conducted without formal credentials, demonstrated a prodigious intellect that challenged established scientific norms.

The Biefeld-Brown Effect: A Radical Hypothesis

The Biefeld-Brown effect, discovered in the 1920s, involves applying high voltage to an asymmetric capacitor, typically with a small positive electrode and a larger negative one, resulting in a net force toward the smaller electrode. Brown theorized this force was anti-gravity, caused by electric fields interacting with Earth’s gravitational field, a concept he called electrogravitics. His devices, such as the gravitator, a block with embedded electrodes, and disc-shaped lifters, visibly moved when powered, fueling his belief in gravity manipulation.

Mainstream science explains the effect as ionic wind, where high voltage ionizes air around the positive electrode, creating charged particles that flow to the negative electrode, transferring momentum to air molecules. Tests in high-vacuum chambers showed no thrust, confirming this explanation. Brown’s experiments in partial vacuums, down to a fraction of atmospheric pressure, still produced motion, which he attributed to electrogravitics, though critics argue residual air was responsible.

Brown’s genius lay in his bold hypothesis and meticulous observations. He proposed that high-voltage capacitors could alter gravitational fields, a concept that anticipated later theoretical work on gravitoelectromagnetism. His detailed designs, including complex electrode configurations, reflected a deep understanding of electrical engineering, inspiring amateur experimenters and alternative science enthusiasts to explore his ideas further.

Experimental Milestones: Building the Future

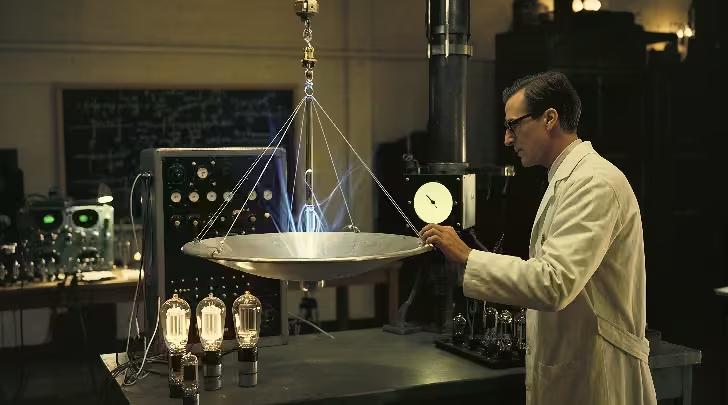

In the 1930s, Brown worked at the Naval Research Laboratory, proposing his gravitator for ship propulsion. He participated in a 1932 Navy-Princeton gravity expedition, testing his ideas, but resigned in 1942 under unclear circumstances. In the 1950s, he collaborated with an industrialist in North Carolina, testing disc-shaped lifters up to 30 inches in diameter. These experiments, captured on film, showed devices circling a mast under high voltage, mesmerizing onlookers.

In 1952, Brown demonstrated two 2-foot-wide metal discs on rotor arms to military and scientific audiences, claiming they defied gravity. A 1956 industry report suggested electrogravitics could achieve supersonic speeds, drawing interest from major aerospace companies. However, a naval evaluation attributed the motion to electric wind. Brown founded a research group in 1958 and worked for a technology firm in the 1960s, filing patents for electrokinetic devices, including one for an advanced propulsion system.

Despite limited funding, Brown’s persistence was remarkable. He spent significant personal resources, equivalent to hundreds of thousands in today’s dollars, on experiments. His detailed documentation and functional devices, though not proving anti-gravity, showcased an engineering brilliance that pushed the boundaries of electrical science.

Military and UFO Speculation

Brown’s experiments sparked rumors of classified military applications. Some speculate his electrogravitics influenced experimental projects, such as a supposed naval teleportation experiment in the 1940s, though no evidence supports this. Others suggest his technology was incorporated into advanced aircraft, like a stealth bomber, due to its use of high-voltage systems. These claims, popularized in alternative science circles, remain unverified but highlight Brown’s influence on speculative narratives.

In the 1950s, Brown briefly worked with a UFO investigation group, leaving amid funding disputes. His Work attracted attention from aerospace firms, with reports from 1956 indicating interest in electrogravitics for propulsion. Some enthusiasts argue that classified programs adopted his ideas, pointing to his secretive experiments and corporate connections. Critics counter that no credible evidence links Brown’s work to operational technologies, and his devices’ motion is fully explained by conventional physics.

The mystique surrounding Brown’s work stems from his own secrecy and the era’s fascination with UFOs. His vision of electrogravitics as a propulsion revolution, potentially mimicking UAP capabilities, continues to inspire alternative science communities, reflecting his genius in sparking bold ideas about advanced technology.

Scientific Critiques: Genius Meets Skepticism

Mainstream scientists have consistently challenged Brown’s anti-gravity claims. Studies in the 1990s and 2000s, including by the U.S. Air Force and academic researchers, found no thrust in high-vacuum conditions, confirming ionic wind as the cause of motion in Brown’s devices. Critics argue that Brown, lacking formal physics training, misinterpreted electrohydrodynamic effects, mistaking air movement for gravitational manipulation.

Brown’s experiments in partial vacuums, which he claimed showed electrogravitic effects, were likely influenced by residual air molecules. Later studies explored electrogravitics but found only marginal effects, insufficient to support anti-gravity. Despite this, some researchers credit Brown with raising intriguing questions about electromagnetic-gravity interactions, noting that his ideas, while unproven, align with theoretical concepts like gravitoelectromagnetism explored in modern physics.

Brown’s genius shone through his ability to inspire scientific inquiry, even if his conclusions were disputed. His detailed observations and willingness to challenge orthodoxy prompted tests by major institutions, underscoring his impact on pushing the boundaries of electrical and propulsion science.

Cultural Impact: Inspiring a Movement

Brown’s work has profoundly influenced alternative science and UFOlogy. His lifter designs inspired a global community of amateur experimenters, who build high-voltage replicas and share results online. Major institutions, including a space agency, briefly explored lifter technology for satellite propulsion, reflecting the seriousness of Brown’s ideas. His concepts also permeated popular culture, influencing science fiction and speculative narratives about advanced propulsion.

Recent discussions in alternative science communities have revived interest in Brown, with some claiming his technology was suppressed or integrated into classified projects. Documentaries and books portray him as a misunderstood genius, whose ideas were ahead of their time. While these claims lack substantiation, they highlight Brown’s ability to captivate imaginations and inspire ongoing exploration of unconventional science.

Brown’s legacy lies in his role as a catalyst for curiosity. His experiments, though not proving anti-gravity, advanced understanding of electrohydrodynamics and inspired a subculture of innovators, making him a pivotal figure in the study of unexplained phenomena and potential NHI technologies.

Why Brown Was a Genius

T. Townsend Brown’s genius stemmed from his fearless pursuit of unorthodox ideas. His teenage discovery of the Biefeld-Brown effect, detailed in multiple patents, showcased an intuitive grasp of high-voltage systems and electromagnetic theory. With minimal formal training, he developed functional devices that moved under electric fields, anticipating concepts like gravitoelectromagnetism decades before they entered theoretical physics.

Brown’s persistence was extraordinary. He invested personal wealth, equivalent to hundreds of thousands of dollars today, and decades of effort, despite skepticism from mainstream science. His ability to attract interest from major aerospace firms and produce detailed documentation reflects an engineering brilliance that transcended academic credentials. His vision of electrogravitics as a universal force, potentially powering UAP-like craft, inspired both scientists and enthusiasts.

Though his anti-gravity claims remain unproven, Brown’s legacy is his ability to challenge conventional wisdom and spark debate. His work continues to inspire those exploring the frontiers of propulsion and the mysteries of the cosmos, cementing his status as a visionary genius in the realm of unexplained phenomena.

Sources

The information in this post was compiled from the following non-Wikipedia sources:

“The Man Who Mastered Gravity: The Story of T. Townsend Brown” by Paul Schatzkin, published 2023, detailing Brown’s life, experiments, and electrogravitics theories.

“Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology” by Paul A. LaViolette, published 2008, exploring Brown’s work and its potential military applications.

“The Philadelphia Experiment: Project Invisibility” by Charles Berlitz and William L. Moore, published 1979, discussing speculative connections to Brown’s technology.

“Electrogravitics Systems: Reports on a New Propulsion Methodology” by Aviation Studies Ltd., 1956, outlining corporate interest in Brown’s ideas.

“Electrogravitics II: Validating Reports on a New Propulsion Methodology” by Thomas Valone, published 2005, analyzing Brown’s experiments and scientific critiques.

“Experimental Investigation of the Biefeld-Brown Effect” by Martin Tajmar, published in the International Journal of Modern Physics, 2004, debunking anti-gravity claims.

Please check out the fantastic Jesse Michels documentary on T. Townsend Brown below: